Parivrtta Parsvakonasana

Note: Touch or hover your mouse over underlined terms for a definition.

The following is a discussion of the position on the right side, as pictured. As an asymmetrical posture, it must be repeated on the left side.

- Parivrtta: Revolved / Twisted

- Parsva: Side

- Kona: Angle

This is the sixth position in the Ashtanga Standing Series.

The essential aspect of this position is a twist of the spine from sacrum to atlas (pictured above left). With practice, additional layers are added, working more deeply in the shoulders, and then finally the hips, until the body twists in a spiral from the outside edge of the left foot, through the thigh, spine, and all the way up the right arm to the fingertips (pictured above right).

In the earlier stages, effort is focused on gaining rotational mobility in the spinal column. The legs and arms remain a relatively passive support and do not fully activate. A number of muscles in the core work synergistically to rotate the spine, including the oblique abdominals, the psoas major, quadratus lumborum, intercostals, and the rotatores.

As flexibility is gained through these spinal support muscles, the movement deepens and effort should be concentrated on relaxing these muscles and creating the force of the twist by leveraging the left shoulder and elbow against the right knee, which allows the spinal muscles to relax and lengthen while the more powerful hip abductor and pectoralis major muscles contract paradoxically. Because both the knee and the arm are immobilized, force is transmitted to the back side of the body, creating torque in the spine.

Contraindications: Any injury in the spine should be treated with great caution. Spinal twists can greatly exacerbate any injury, especially if the back curves (spinal flexion). Neck pain or cervical spine injury: Look forward, do not look up. If you have an injury in the knee or shoulder, modify by slightly bending the joint or finding a comfortable position. If placing the knee on the mat causes pain, it can be eased by placing a towel or blanket beneath the knee or moving the knee backwards and straightening it slightly (extension), increasing the angle between the upper and lower leg.

Stage 1:

From Samasthiti, inhale and step your right foot back ~3′ and pivot the body 180°, bringing the hips fully square towards the rear of your mat — press the left hip forward and the right hip back. Place the left knee on the mat, keeping the toes tucked and the ball of the foot on the mat. Lift the left elbow high. Exhale fully as you twist, hooking the left elbow as low as you can on the right leg, bringing the armpit and rib cage as close to the knee as possible.

Press the palms together firmly and twist the torso to the side. Look up towards the ceiling.

Press the upper arm and knee together firmly, moving the knee towards the side of the mat, to deepen the twist.

Take 5 deep exhalations, then, in two separate movements*, slowly untwist then lift to a standing position. Pivot to face the front and repeat these steps on the left side.

Note: This position can also be entered directly from the previous asana, Utthita Parsvakonasana, without returning to Samasthiti.

*Lifting the weight of the upper body to an upright position while still twisted places the lumbar spine in a vulnerable weight-bearing position.

Stage 2:

As described in Stage 1, but straighten the left leg, lifting the knee off the mat. Keep the left toes pointing forward, reaching back through the heel.

Stage 3:

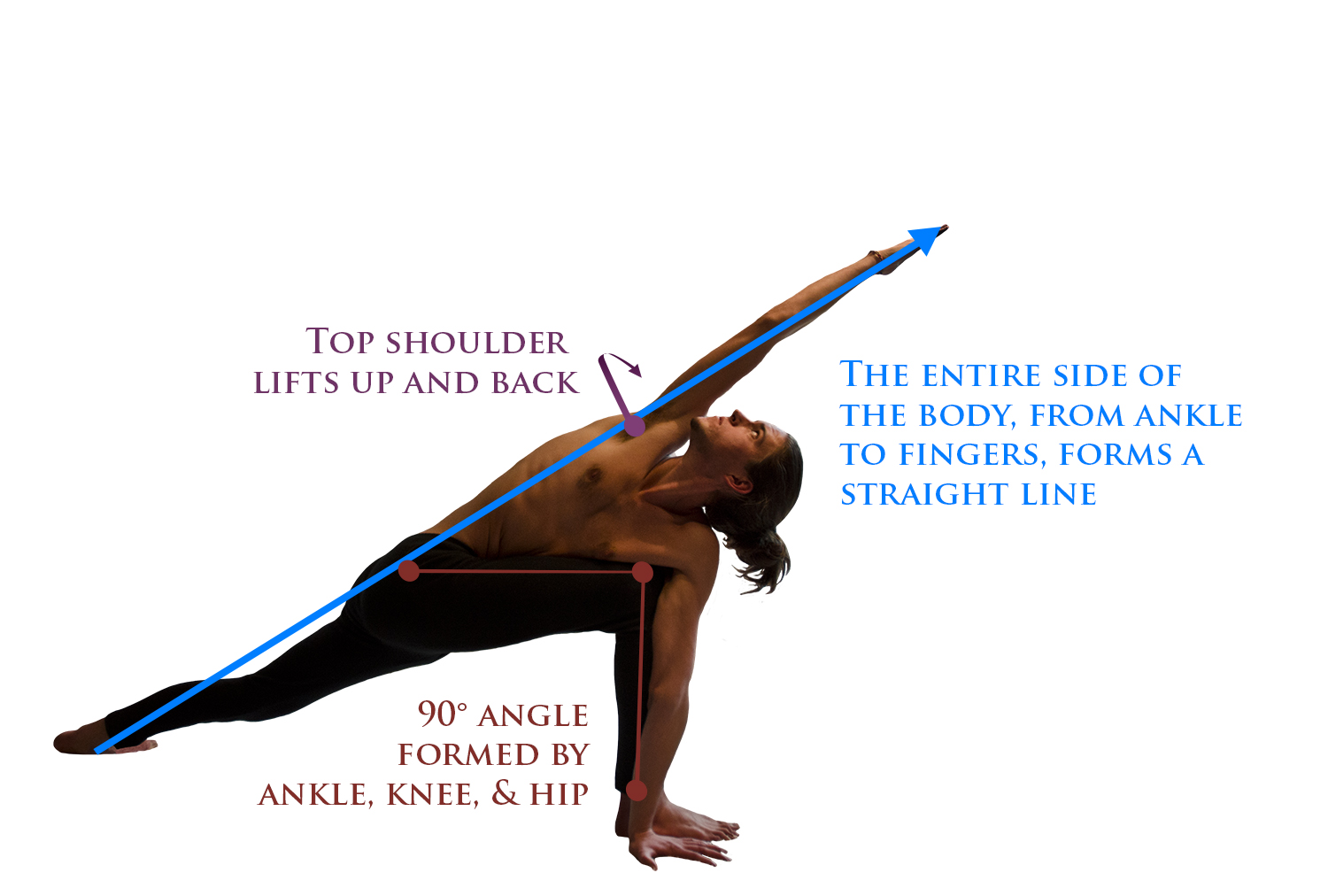

From Utthita Parsvakonasana, lift to neutral and pivot to face the rear of the mat. Keep the left foot facing out at a 45° degree angle, with the sole of the foot pressing firmly into the mat. Both heels are in line. Square the hips, then exhale as you bring the left palm down to the mat on the outside of the right foot. Raise the right hand towards the ceiling and straighten the elbow fully. Turn the palm to face the mat and extend the arm overhead. Press the right knee into the left shoulder to create the force of movement to twist the spine. Gaze up to the right fingers.

If reaching to the ground is too much, you may place your hand on a block. Be wary of relying on props, and reduce the height of your support regularly.

Take 5 deep exhalations, then inhale to a standing position. Pivot to face the front and repeat these steps on the left side.

Analysis

As discussed above, the main focus of this asana is a twist of the spine. Stage 1 is a distillation of this essential movement. Stage 2 challenges balance and works to strengthen the legs. When progressing to Stage 3, the entire body becomes involved with the twist. Try twisting a washcloth, as if to wring water out. To create force in the center of the cloth, you will twist the ends in opposite directions. Similarly, the left leg and right arm rotate in opposite directions to intensify the twist in the torso. The left foot is turned out 45°, creating an anchor for the twist through the leg. The hips are square, ensuring that we are working between the left leg and the left hip (challenging the quadriceps and hip adductors), rather than twisting the left hip relative to the right hip. One of the main aspects of progression here is the position of the left foot. The right foot stays in the same position for all 3 stages.

- Stage 1: Left knee on the ground, ball of the foot pressing into the mat.

- Stage 2: Left knee lifted, ball of the foot pressing into the mat, heel lifted and pressing back.

- Stage 3: Left leg rotates 45°, bringing the sole of the foot and the heel down to the mat. This rotation of the foot brings both heels in line.

Picking Your Stance

In advanced stages of practice, Virabhadrasana II (Warrior II), Utthita Parsvakonasana (Extended Side Angle), and Parivrtta Parsvakonasana (Revolved Side Angle), all share the same stance. The exact foot placement depends on leg length, but will typically be quite wide, between 3-5 feet. A 3 foot stance would be appropriate for someone 4-5′ tall, while someone 6′ or over would require a 5′ distance between the feet.

A couple rules of thumb apply to all practitioners:

- If the knee begins to reach in front of the ankle or over the toes (less than 90° angle in the knee), the stance is much too short.

- If the hips are lifting up above the level of the head, the stance is much too short.

- If your back knee is on the mat, walk the knee back as far as you can into a ‘lunge’ position.

- If you feel wobbly, spread the legs to hip distance or more width-wise on the mat.

Spinal Alignment

In the pelvis, the spinal twist begins with the sacrum. In advanced practice, the spine may rotate a full 180°. Ideally, the sacrum will have a few degrees of rotation at most. In many practitioners, this area may be ‘frozen’ by severely tightened pelvic ligaments and a chronically overcontracted piriformis.

The twist continues up the spine, with a few degrees of rotation at most from each lumbar vertebrae. It is best to focus on lengthening, rather than rotating, the lumbar spine as it is not well suited to twisting. A much larger amount of rotation comes from the rib cage, and finally the cervical spine twists to allow the gaze to move upwards.

As with any spinal twist, it is important that the spine be kept neutral in all planes of movement except rotation. This applies to both Stage 1 & 2. Tightness through the hamstrings and lower back will manifest here, as with any forward fold. These compensations can commonly be observed in those who bend at the waist rather than the hips.

The most common accessory movement here is flexion of the spine, with the back rounding or curving forward. This is a very dangerous combination, as the combination of flexion and twisting is the most vulnerable position of the lumbar spine. Flexion is typically a compensation for tightness in the hamstrings or a pelvis frozen in posterior rotation, and shows that the lower parts of the spine – the lumbar and sacral – are not working in conjunction with the two upper sections of the spine. This movement can be corrected by focusing on rolling the hips up and forward (into anterior rotation) and beginning the twist from as low in the spine as possible. Ensure that there is no gap between the navel and thigh.

A second common accessory movement is lateral flexion from the thoracic spine – bending from the waist to the side, a compensation to bring the shoulders lower. Lifting from the bottom of the rib cage will lower the top edge (the collarbone & shoulers), allowing an extra few inches of reach through the arm. This movement masks tightness in the lower spine and pelvis. A common symptom of this compensation is feeling as if you’re only breathing into the right (top) side of the lungs and the left (bottom) side is compressed. Correct this by pressing the bottom left ‘wing’ of the rib cage down into the thigh and focus on breathing into and expanding the left lung.

Shoulders & Arms

Engaging the muscles of the back will serve to compress, rather than lengthen and twist, the spine. This explains the importance of the hand position. By stabilizing through the shoulders and upper arm, the force of the twist can be generated by pressing the knee firmly against the upper arm. If the palms are pressing together, the effort is focused mostly into rotation of the rib cage. If the hands are extended as pictured, the muscles around the shoulders and neck are being addressed at a deeper level; placing the hand near the foot also requires a large degree of rotation from the thoracic spine. By lengthening the arms (straightening the elbows), the muscles in the shoulder are more fully engaged because they are being stretched from both ends while contracting. Keeping the arms bent and the palms together allows the muscles of the shoulders to relax more.

The fingertips of the left hand are aligned with the right toes to balance two opposing alignments in the body: keeping the shoulder and arm aligned at 90°, and keeping the knee and shoulder together. Bringing the hand farther back towards the heel would hook the shoulder more deeply over the knee, but would create a potentially damaging angle in the wrist joint. Putting the wrist at less than a 90° angle in weight bearing positions should be approached very cautiously. If, instead, the hand were moved forward of the toes, the shoulder and knee would no longer be in position to press together to create the force of the twist (unless, of course, the knee were moved forward over the toes–which would be harmful to the knee joint.

Once you feel stable, press down through the left hand and lift up through the right shoulder, broadening the space between the shoulderblades. Ensure that the shoulders stay strong and wide, rather than collapsing in around the neck.

Common Mistakes:

Mistakes are relatively infrequent in this position, and stem mostly from lack of flexibility and will thus be corrected over a period of time as flexibility increases.

The most frequent instability in this posture is flexion of the spine, as described above, which can be improved by focusing on lengthening and folding from the hip.

The knee may attempt to creep towards or over the midline of the body, to balance inflexibility in the shoulders, with the knee moving out over the mat instead of the ankle. Typically, putting weight into the front leg before beginning the twist will stabilize the knee joint, but if you notice this happening, focus on moving the knee to the side, pressing it into the elbow as discussed above, until it is centered above the ankle.