Parsvottanasana

Note: Touch or hover your mouse over underlined terms for a definition.

The following is a discussion of the position on the right side, as pictured. As an asymmetrical posture, it must be repeated on the left side.

- Parsva: Side

- Uttana: Stretched / Spread out

- Asana: Position

This is the eighth and final movement of the Ashtanga Standing Series.

Following the symmetrical stretching of the hamstrings in the previous position (prasarita padottanasana), the hamstrings are now lengthened asymmetrically. The elements of backbending essential to all forward folds (the lifting and broadening of the front body, especially the arc of the collarbones) is encouraged by the positioning of the hands between the shoulder blades. The essential aspect of this pose is, like all forward folds, a lengthening of the hamstring muscles and rotation of the pelvis. The entire back side of the body, from the heels to the hips, down the spine to the neck, lengthens and relaxes while the front side of the body takes the effort of balancing.

Contraindications: Any injury in the spine should be treated with great caution. Lumbar injury, especially, may be exacerbated by performing this position incorrectly. Rounding of the spine (see: ‘Common Mistakes’, below) can place a great deal of stress on the vertebrae. If you’re practicing with an injury, seek the guidance of an instructor to ensure that this position is performed healthfully. If you have a condition that affects your heart or blood pressure, be careful with bringing the head lower than the heart, which may induce dizziness. The placement of the hands may exacerbate injuries to any of the 4 joints of the shoulder.

Stage 1 Variation

From Samasthiti, step the right foot back, pivot on both feet to face the rear of your mat. Take a relatively short stance, 2-3 feet. The left foot is angled 45° towards the left. Ensure that the right big toe is straight forward, and not angling towards the right.

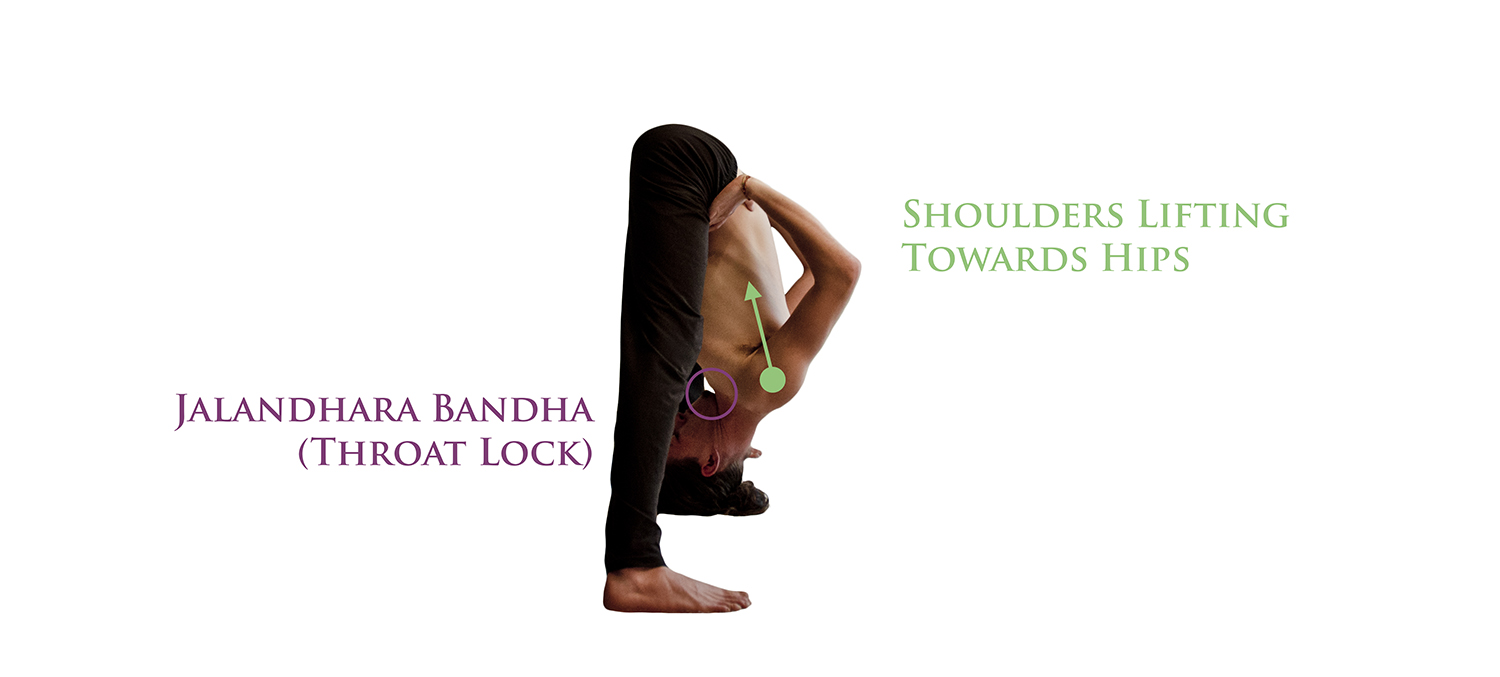

Wrap the left hip around towards the right thigh, turning the pelvis fully. Grasp opposite elbows behind your back. Squeeze the shoulder blades together and towards the hips (the action of the rhomboid muscles) to encourage the broadening of the front of the rib cage. Do not allow the shoulders to droop around the neck.

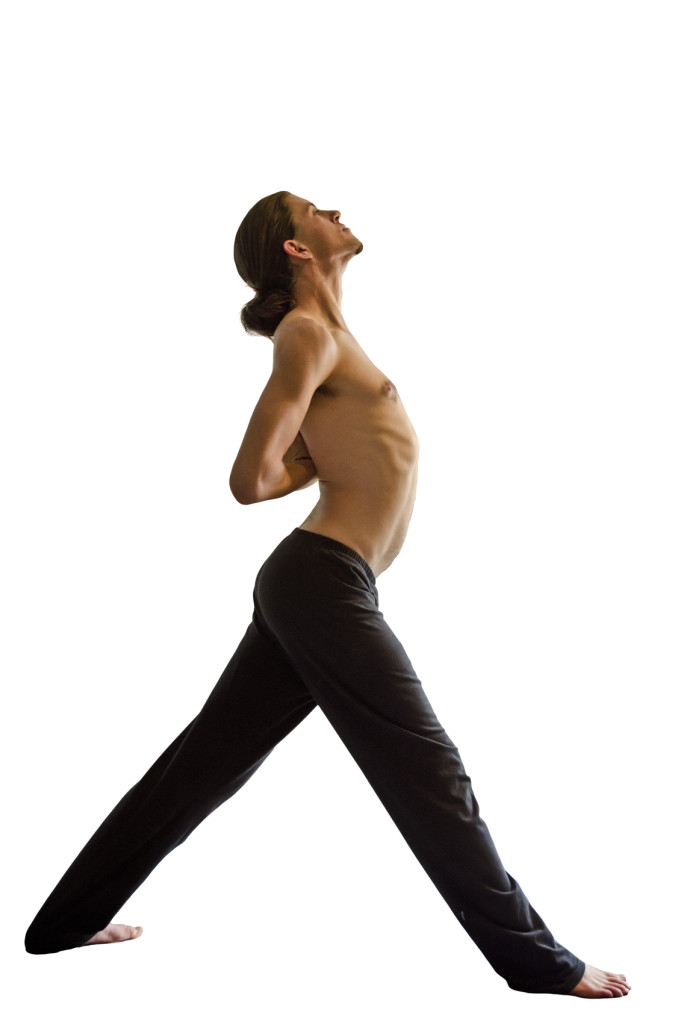

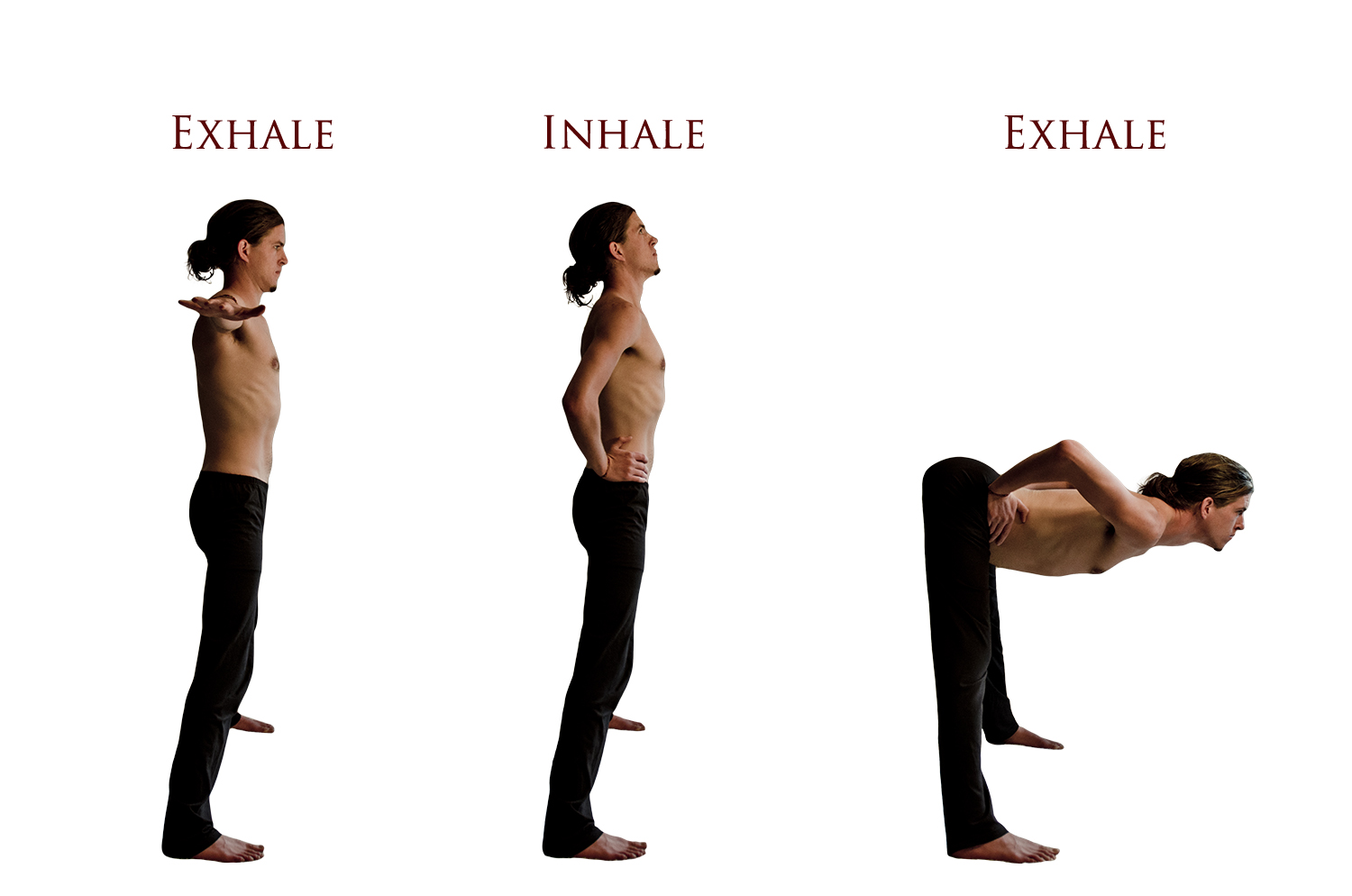

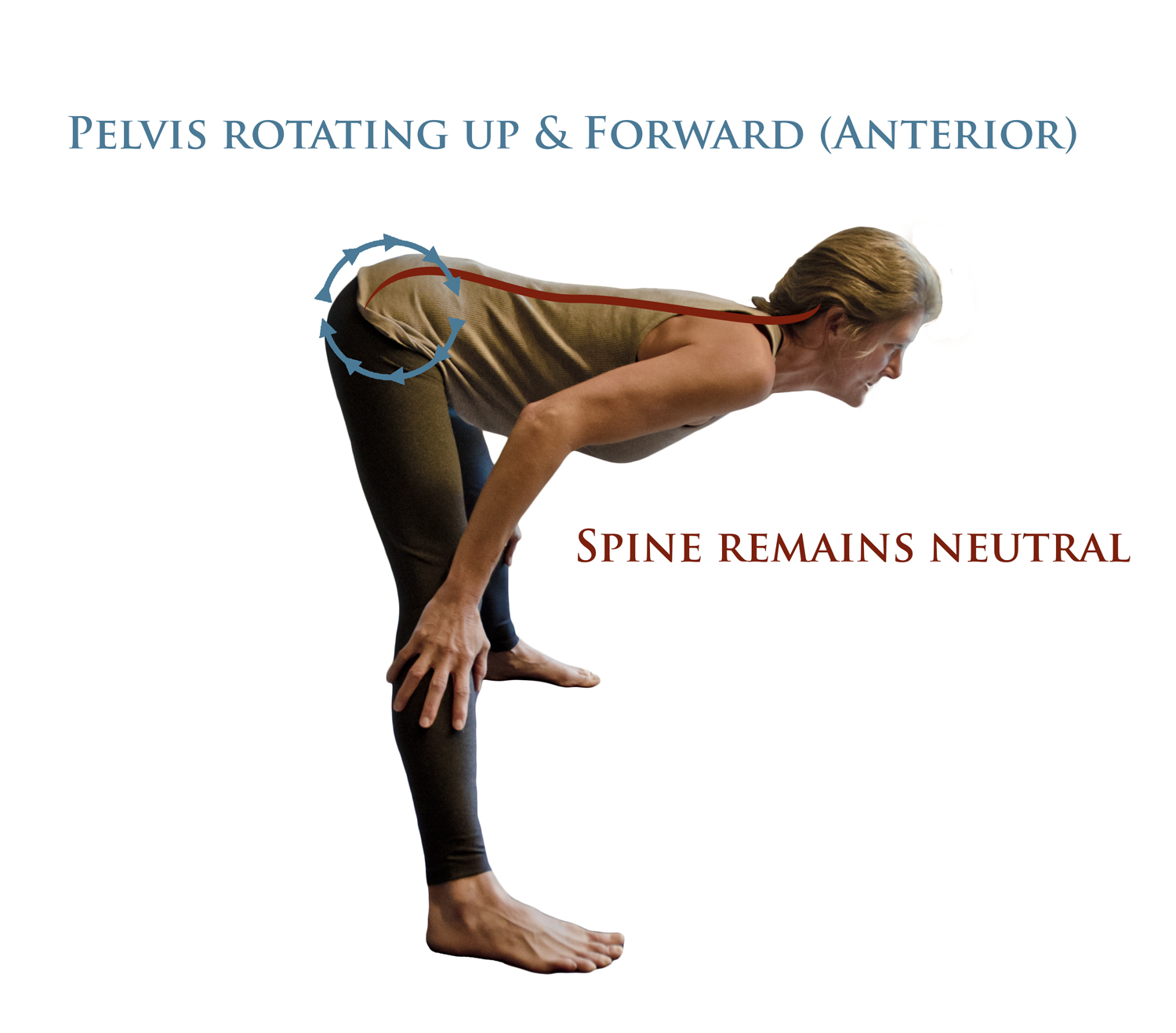

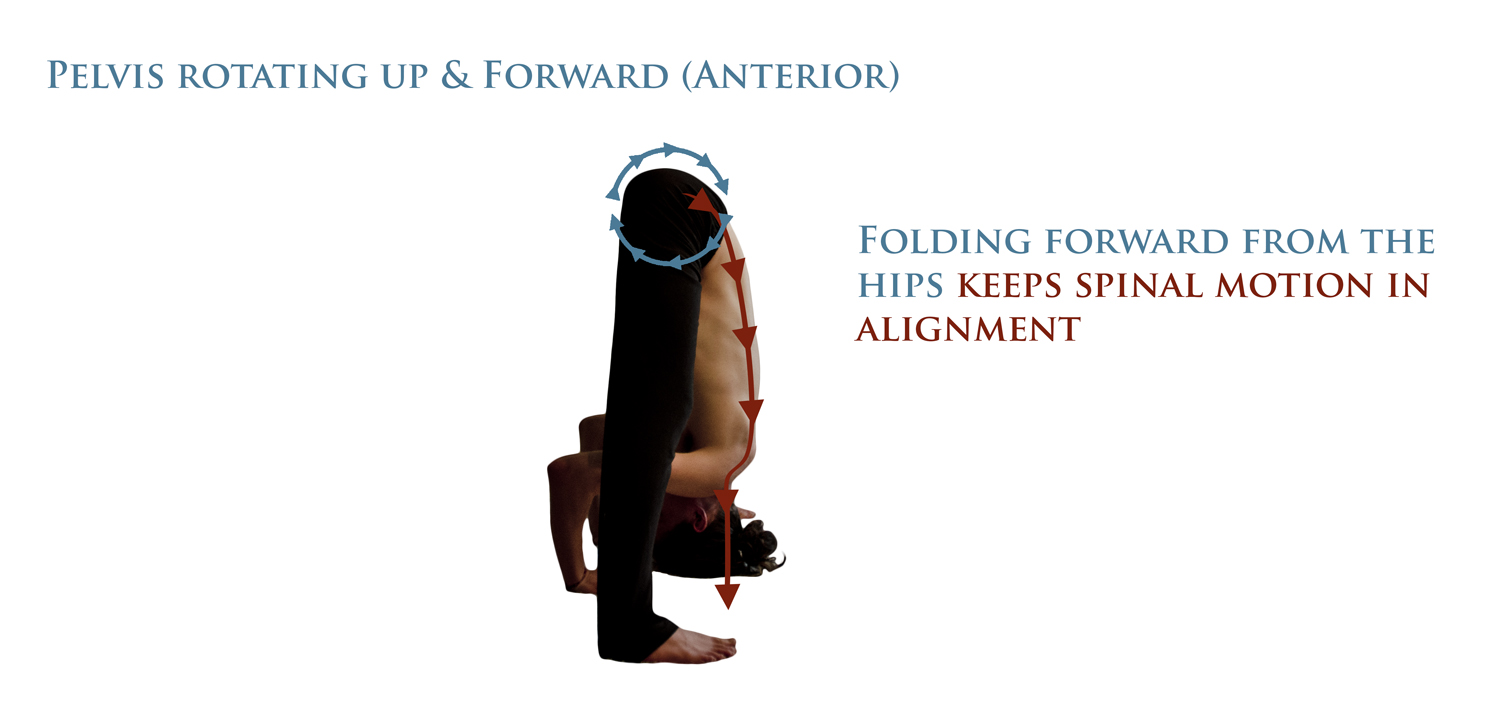

Inhale and arch the spine, looking upwards (pictured below) and lifting the rib cage and head vertically towards the ceiling to elongate the lower back. Keep this length as you fold forward, deepening the right hip crease. Be careful to only create this motion by the rotation of the pelvis — the upper body stays broad and active, resisting the movement by lifting towards the ceiling. Stop shy of the point where the back begins to round or curve.

Stay here for 5 breaths, then inhale to standing. Exhale, pivot to face the front, repeat on the left side for 5 breaths. Inhale to standing, exhale to Samasthiti.

Parsvottanasana

From Samasthiti, step the right foot back, pivot on both feet to face the rear of your mat. Take a relatively short stance, 2-3 feet. The left foot is angled 45° towards the left. Ensure that the right big toe is straight forward, and not angling towards the right. Keep the pelvis square — don’t allow the left hip to fall back. Press the palms together behind the back, between the shoulder blades.

Inhale and arch the spine, looking upwards (pictured below) and lifting the rib cage and head vertically towards the ceiling to elongate the lower back.

Keep this length as you fold forward, deepening the right hip crease. Be careful to only create this motion by the rotation of the pelvis — the upper body stays broad and active, resisting the movement by lifting towards the ceiling. Stop shy of the point where the back begins to round or curve, or the shoulders begin to draw together in front of the chest.

Keep both thighs rolling gently inwards, pressing the inner arch of the foot and the big toe mound into the ground. Do not allow weight to rest into the outer edge of the right foot, or the big to begin to turn out towards the right side. This serves to keep the hips moving towards square and prevents the asymmetrical stretching of the knee, which over time could create instability or pain. If the toes are turned out to the right, the tibia is typically rotating more than the femur, a difference made up for by a twisting of the knee joint itself (which is not well suited to rotation).

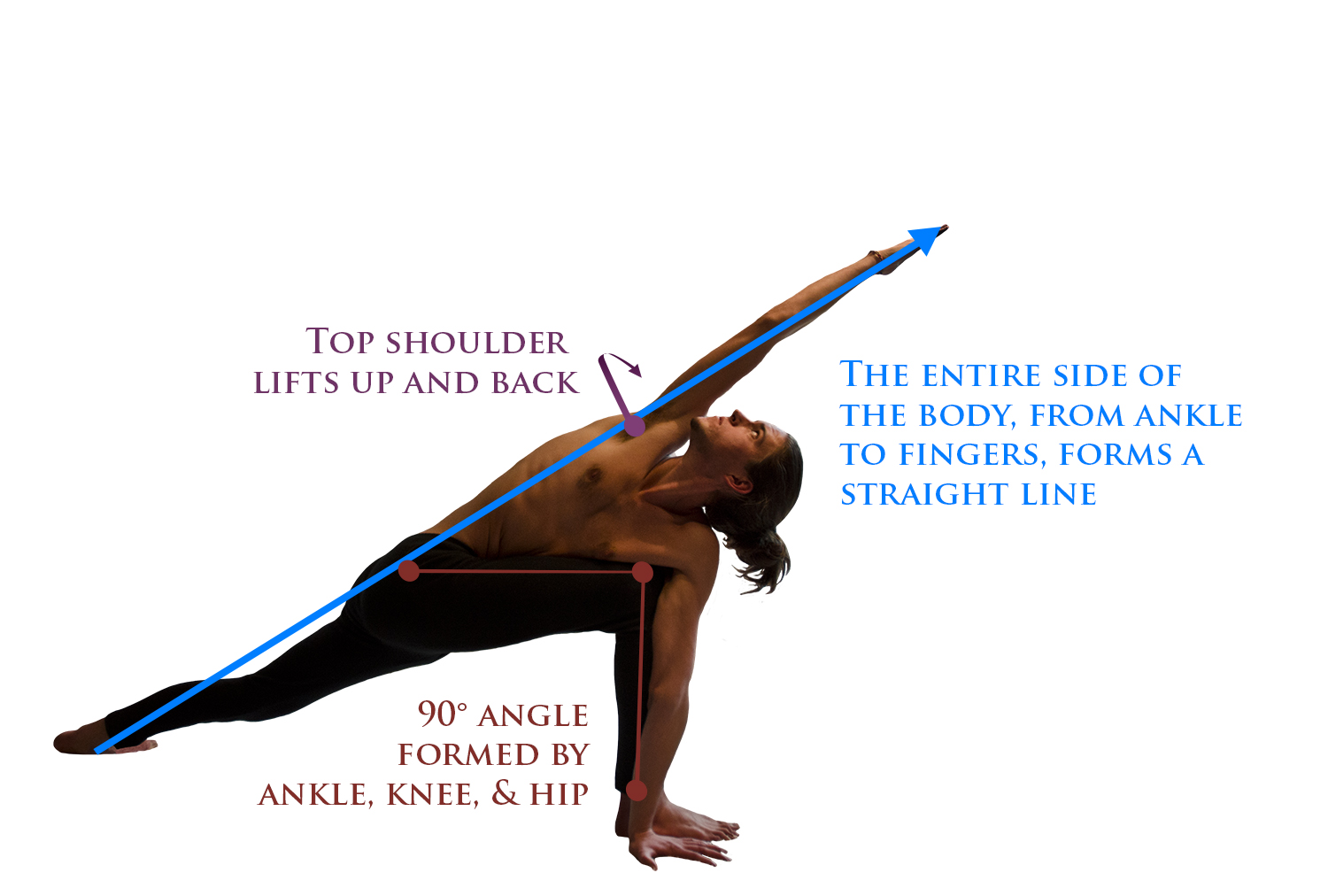

Lift the elbows towards the ceiling, away from the torso, to support the rotation of the head of the arm bone away from the sternum (external rotation of the humerus).

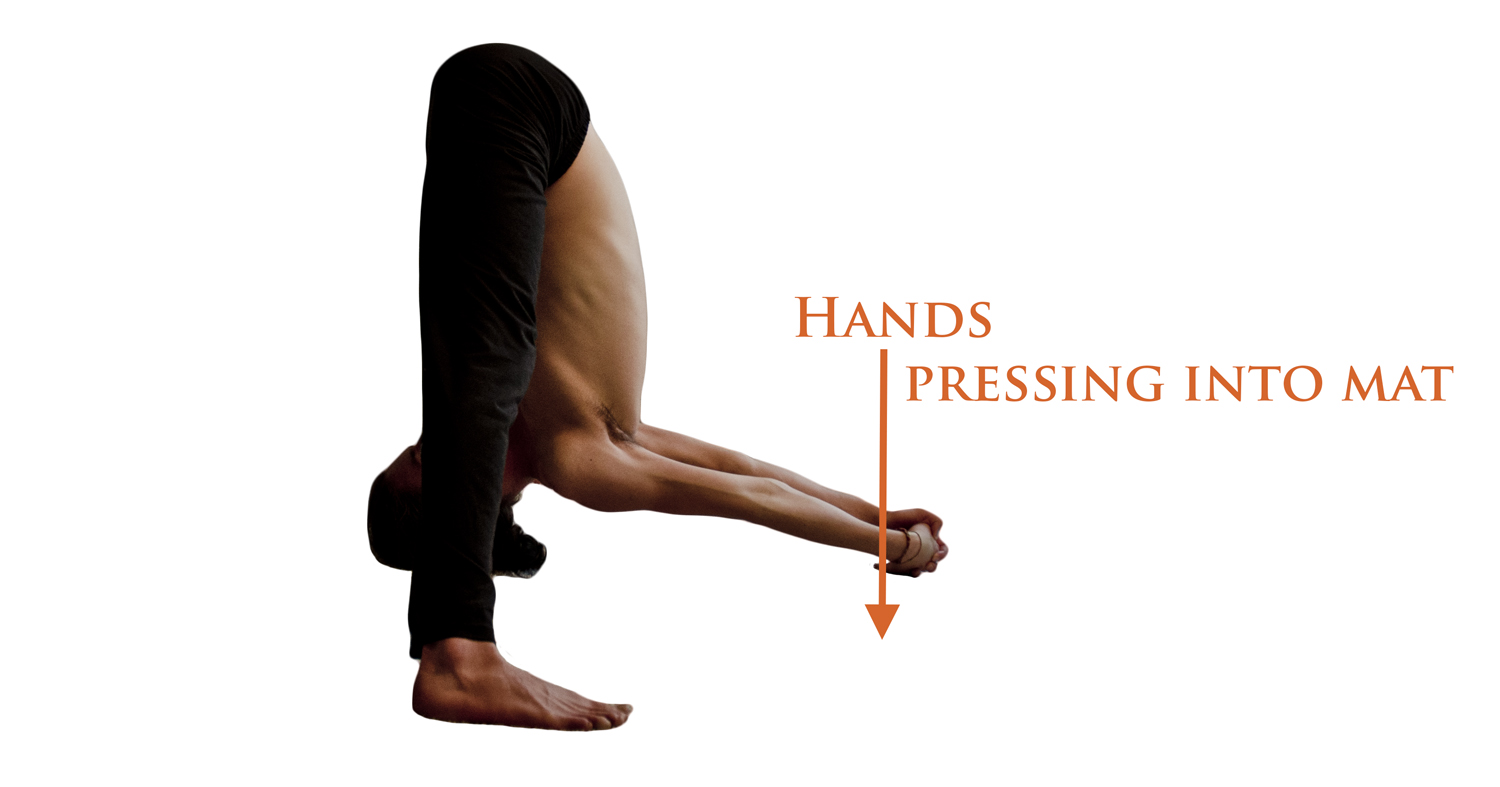

Lengthen the spine along the leg towards the toes.

The action of the bandhas is essential here to allow the elongation of the spine while maintaining balance.

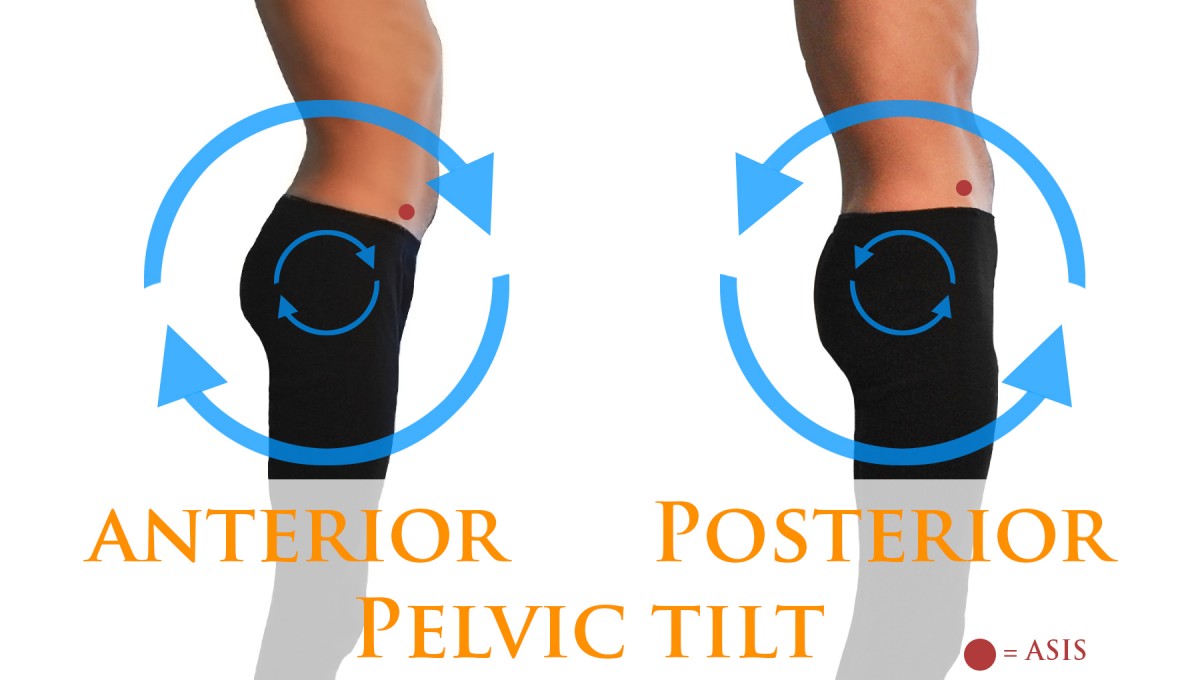

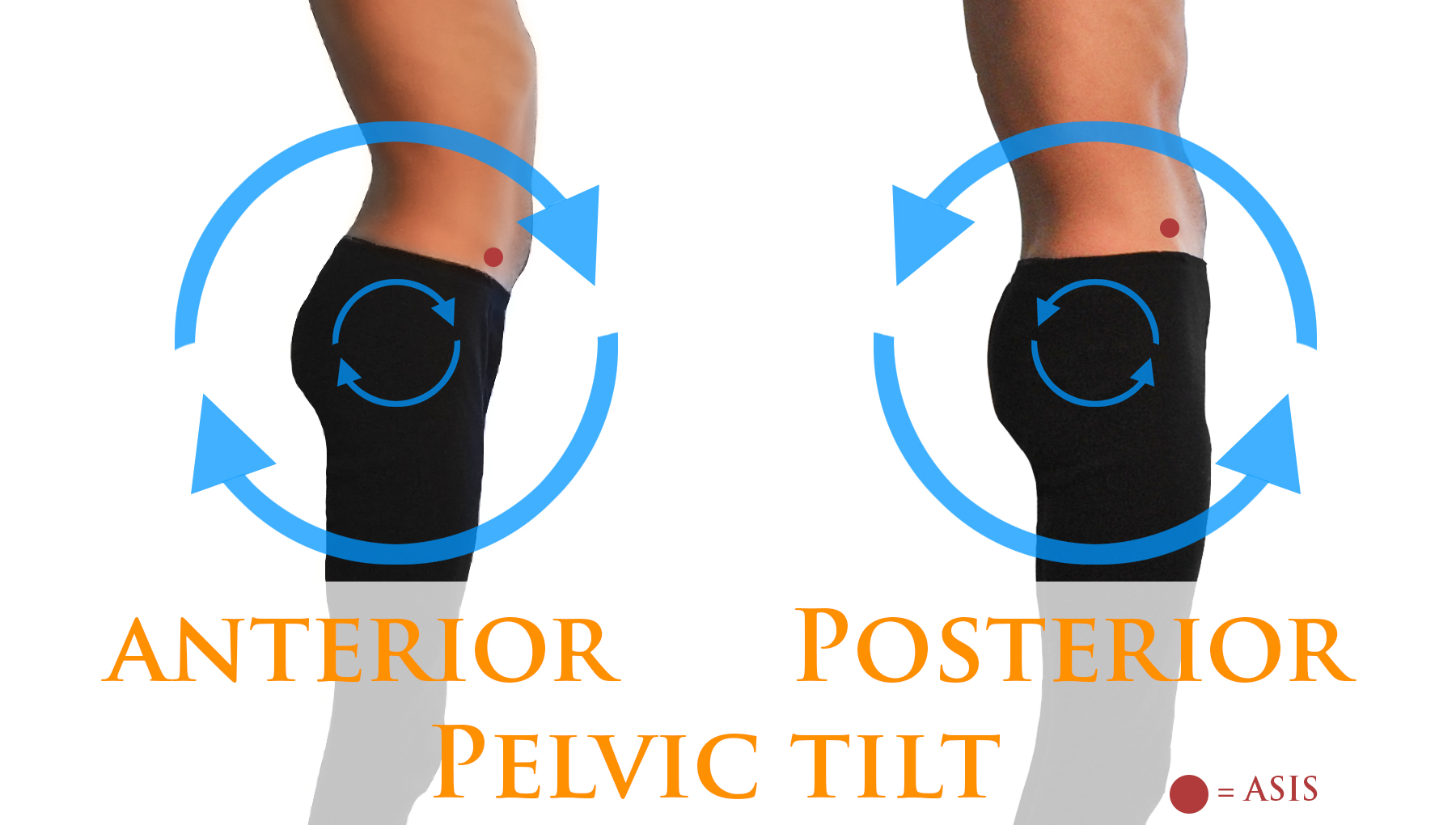

Weight has a tendency to shift into the front foot. This will bring the hips out of alignment (see common mistakes below), and consequently, the entire spine will rotate. Counteract this by pressing down firmly through the left (rear) foot, shifting your weight backwards. You will feel the quadriceps engage, especially as a feeling of stability around the knee. This serves the dual function of stabilizing the leg and tipping the pelvis forward (anteversion) to bring the sacrum forward into alignment with the length of the spine.

Keeping the neck in extension (looking towards toes as pictured above) should only be attempted if the cervical spine is competent. If the neck is not functioning properly, the vertebrae collapse as the head tilts back and compresses the back of the neck. A healthy extension of the neck demands action from all the cervical vertebrae and the musculature of the front of the throat. Gently press the forehead towards the foot and focus on Jalandhara Bandha at the throat – it should be assisting in creating a steady Ujjayi breath and engaging the muscles that stabilize the vertebrae. If you have any neck injury, feel like the back of your neck is shrinking or pulling into the shoulders, or that the skull is simply tipping back loosely atop the spine, instead look towards the toes of the rear foot. This will keep the neck in alignment with the rest of the spine, where it is more protected.

Press the palms together firmly to keep the arms active, encouraging the opening of the rib cage and the broadening of the area around the collarbones.

Stay here for 5 breaths, then inhale to standing. Exhale, pivot to face the front, repeat on the left side for 5 breaths. Inhale to standing, exhale to Samasthiti.

Common Mistakes

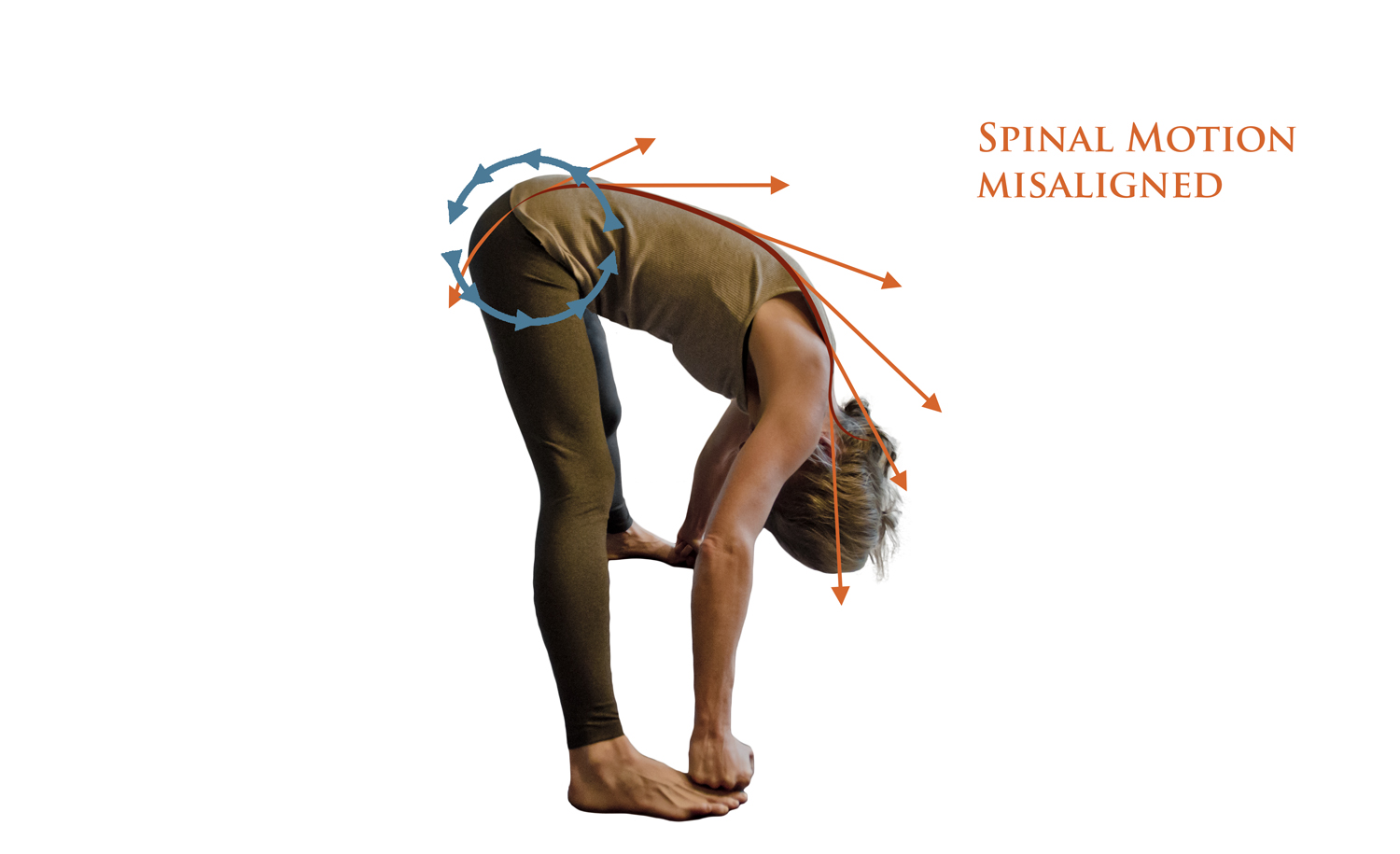

The most common misalignment in this position is, as mentioned above, improper positioning of the hips. Weight coming forward into the right (front) foot will tend to elevate the right hip and depress the left. This will cause the entire spine to rotate or bend laterally to compensate and maintain balance.

This misalignment can also be seen with the opposite motion in the hips – right lip dropping, left hip lifting high. It may lead to the same position of the shoulders as an overcompensation.

Correct either by lifting to standing, and keep your weight rooted firmly into the rear foot. Focus on keeping the hips level vertically, lifting the left hip towards the ceiling. The action of mulhabandha (root lock) will help create the lift in the hips.

This is another common position:

Here, the stance is too short, bringing the weight almost entirely into the front leg. The pelvis gets “stuck” and rotates backwards, pulled by the right hamstrings. This causes or exacerbates kyphosis of the spine, putting extra pressure on the lower back and allowing the upper body to droop downwards. This is an unhealthy position for the right knee, right hip, and lower back. It also tends to emphasize the rounding of back (kyphosis) already common in many practitioners.

For a more in depth analysis of the biomechanical action of forward folding, refer to Prasarita Padottanasana (Wide-Leg Forward Fold) or Understanding Pelvic Tilt, where the topic has been explored extensively.

From

From